Patriotism or Prestige

What is the true motivation of generals?

Bryan Caplan had a great post about whether public servants are motivated by civil duty or a will to power, can be revealed in a natural experiment: Supreme Court judges almost never choose to retire early and let a younger judge, friendly to their cause, take their place; instead, they hold on to power, sometimes to their dying breath.

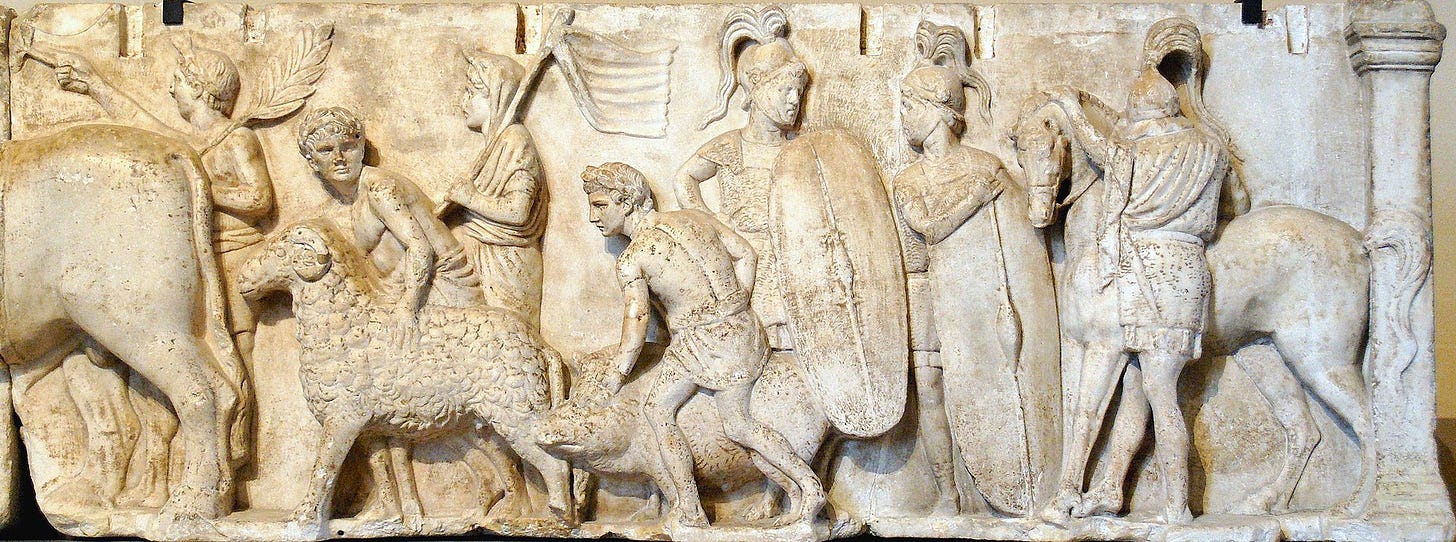

I was thinking about a similar natural experiment regarding generals. Generals are often portrayed as motivated by a deep duty toward their country, the ancient sources are full of such descriptions:

Plutarch tells us that when Aristides "the just", who was instrumental in setting up the Delian League/Athenian Empire, was responsible for the public treasury, he would supplement any missing funds with his own money and would pay himself back if any extra funds were discovered (I could believe half of that).

We are told by Nepos that Epaminondas, the general who defeated the Spartans and set up Boethian hegemony in Greece, responded to a Persian bribe by stating:

We are even told that when Themistocles, the victor in Salamis, who defeated and defected to the Persians, was ordered by the King of Kings to attack Greece, he could not bear the task and committed suicide by drinking bull’s blood (which is not toxic).

The alternative explanation is given to us in the motives of one man, whom even the ancient world could not help but to treat with a measure of cynicism.

That is prestige, glory, and the imperishable fame that comes with the job, along with having writers and poets say splendid things about them and getting a month or two named after themselves (or all of them in the case of Commodus).

The Choice

Generals often face the choice of whether to attack the enemy alone and reap the full glory of success or to work together with another general, which would increase their odds of victory but would mean sharing the triumph.

While I do not have the ability to go through and quantify all instances when that choice is present, that exact dynamic existed in three of the most important battles in the history of Rome since the Punic War, showing it was neither marginal nor inconsequential.

Around 113 BC, Rome would face a massive Germanic invasion from Jutland by a tribe called the Cimbri. Together with their neighbors, the Teutons, they would ravage the borders of the Roman Empire, killing tens of thousands of legionaries. To face them, Rome gathered an 80,000-strong army, divided under the leadership of Consul Gnaeus Mallius Maximus and Proconsul Quintus Servilius Caepio. Caepio decided he could take on the Germans alone. He attacked with his half of the force and got everyone there killed (except himself), which isolated Maximus' part of the army and got them killed.

This was the worst disaster that the empire has suffered since Cannea, as a matter of fact, it was as big a disaster as Cannea, if not worse. Afterward, with the Cimbri marching toward the borders of Italy, unprecedented dictatorial power would be placed in the hands of Gaius Marius, who would completely reform the Roman military.

Marius himself was far from being the embodiment of civic virtue; nearing 70 and still glory-hounding, he would steal a command post from his former lieutenant, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, which would precipitate a civil war between the two.

Could the next disaster be even worse? Sure, how about the fall of Rome? In 378, the Goths were invading, advancing toward Adrianopolis with 10,000–20,000 men. Valen, Imperator Romanorum, while moving to stop them, received a letter from his niece and emperor of the west, Gratian, that he was coming to aid him. The problem was that Gratian already got his victory against the Lentienses, it was Valen's time to shine, so he attacked alone and got most of his army killed (including himself). Ever since then, the Goths were a permanent feature of the inside of the Roman Empire and would play a significant part in the collapse of its western half.

How could things go down from here? Well, we still have half of the empire left, and that half would come under threat from a massive invasion of the Saracens, who would conquer most of the east spreading the religion of Muhammad.

After several defeats of a large number of legionaries stationed next to the borders of the empire, Emperor Heraclius ordered a large force to be assembled under two generals, Theodore (brother of the emperor) and the Armenian Magister militum, Vahan. After an initial encounter with the Arabs, Vahan and Theodore quarreled, the Armenians proclaimed their own general emperor, and Theodore left. When the Arabs attacked Vahan had to face them alone and lost. This was the battle of Yarmuk, the most significant defeat the Byzantines experienced against the Arabs, after which Heraclius, hard-pressed to recruit another army, would be forced to leave much of the east to fend for itself for a while (he would also somewhat lose his mind). Of course, the eastern empire would never recover, and so Istanbul is not Constantinople (yes, I am aware of Manzikert).

Other, less "natural experiment style" moments of ego over empire were also common; in the battle of Cannae, the Romans placed two generals over the army who would alternate command every day; in the battle, each commanded from its separate wing instead of the center which got them killed or ran out of the battlefield leaving the army with no command at all. Lest anyone think the moderns are superior, in WW2, the US Navy and Air Force, unwilling to have any of their cryptographic teams placed under the other divided the work between them, one decrypted messages received on even days and the other on odd days. This continued until FDR ordered them to cooperate, unwilling to take separate briefings by each of them.

The true measure of your morality is what you sacrificed for other people.

By that standard, most leaders are failures. I suspect most founders of states, war heroes and freedom fighters had far less noble motives than is commonly claimed. Allow me to add to your piece two (admittedly extreme and well-known) examples:

Napoleon never put the interests of the French above his own. All his toils were merely the self-inflicted result of his relentless ambition. That became most obvious after his disastrous Russian campaign, when he rejected multiple peace offers, claiming that this would be too dishonourable. His lust for warfare was so great that eventually his opponents realised that a lasting peace with France would be impossible as long as Napoleon was in power and consequently declared war on him personally, rather than his country. They were right, as later events would prove. Even after Paris had fallen, Napoleon still considered military operations. A year later, he invaded the Low Countries to fight for his throne instead of seeking exile in the United States.

Hitler, of course, was much worse. A draft-dodger in his youth, he had never even payed taxes when he took office, and never would. This is not unremarkable because as a Nazi, he espoused and claimed to embody the most extreme form of patriotism yet invented. His public image painted him as a selfless man who had sacrificed all of his personal life for the benefit of the German people. In contrast, he did not even make a serious effort to overcome his natural shiftlessness while in office. After Stalingrad, he knew the war was lost, but continued it for years until the Russians were about to capture him in his bunker. He only committed suicide because he was afraid of what they might do to him. In his last days, he even declared that the German people had proven themselves weaker than the races of the east, to whom the future now belonged. Since they had failed (him, presumably), he ordered the entire country to be destroyed, since it deserved no future.

Sure, if we look in the history books, we're going to find people who are largely in it for their own glory, and you've ably pointed at some of the failure cases of the bare fact of "immortal glory in stories and memories exists" distorting people's incentives. And this was a particularly Greek and Roman thing, this obsessions with immortality in memory and story!

But isn't this selection? Don't most generals just actually do their jobs? And don't we have just as many "good general" stories in Roman history? Cincinnatus, Cunctator, Scipio Africanus, and much more.

And even if we look at the "great men," the glory-greedy empire builders like Napoleon or Alexander or Genghis Khan, didn't they have loyal generals and subordinates who faithfully did their job, often at a really high standard, and this was a large part of their success?

Genghis' Tsubodai, Alexander's Craterus and Seleucus, and I don't know enough about Napoleonic history there, but I'm sure he had somebody.

I feel like most generals in most countries just largely did their jobs, sometimes well, sometimes badly, but doing it badly SPECIFICALLY for personal glory at the cost of state and countryment is probably relatively rare.